Juniper Publishers- Journal of complementary medicine

Purpose:Student and clinician burnout in the

health professions have been reported across the education spectrum.

Burnout has been linked to medical errors and decreases in performance.

Increasingly over the past two decades, health professional schools are

implementing mindfulness-based stress reduction courses. Since 2010, the

University of Washington has offered an inter-professional mind-body

skills course to graduate students in the health professions. This study

examines the longer-term impacts of experiential mind-body skills

training on graduate health professional students. The objectives of

this 7-year follow-up study, the first of its kind, were:

1. To determine the value that medical, nursing and

pharmacy students retrospectively attribute to an eight-week mind-body

medicine course, for personal and professional development and for

ameliorating chronic stress

2. To determine the extent to which former students would recommend a similar instructional experience for their peers.

Method:An online follow-up survey was

disseminated in late 2016 to early 2017 to 319 potential respondents who

had taken the course between 2010 and 2017. We filtered the results

into subsets based on the type of student.

Results:Results suggest that most students

retrospectively ascribed beneficial effects to having been exposed to a

variety of meditation techniques, particularly mindfulness and

meditation practices.

Conclusion:Most former students ascribed

beneficial effects to learning mind-body skills during graduate school.

We conclude that such offerings may contribute to the development of

more resilient health professionals. We suggest offering similar

elective mind-body skills courses to students in the health professions

programs (246 words).

Keywords: Mind body skills; Stress mitigation; Resilience; Chronic stress

Student and clinician burnout have been reported

across the medical education spectrum [1,2]. Disconcertingly high rates

of student burnout, defined as constellations of symptoms associated

with a professional practice that can result in emotional and personal

exhaustion and/or disillusionment, have

been reported [3-5]. Within medical, nursing and pharmacy school

environments a myriad of stressors exist that can result in acute and

chronic stress that in turn can lead to personal burnout [6-13].

Clinician burnout has been associated with increases in clinician

medical errors [14-15]and overall decreases in performance [16]. Authors

from the fields of medicine, dentistry,nursing, and social work have

called for multiple approaches to

address the problem of burnout [12,18]. Although burnout was

documented among practicing pharmacists many years ago

[2] little appears to have been done to alleviate the stresses of

pharmacy education or practice.

With increasing frequencies over the past two decades

medical and professional schools have started offering

mindfulness-based stress management and stress reduction

offerings [19-23]. Studies examining the efficacy of mindfulnessbased

stress reduction programs suggest that they can lower

levels of psychological distress in medical students [19,24,25].

An elective mind-body skills (MBM) course was first offered at

the University of Washington (U_) in the 2004-05 academic year.

This was an attempt to ameliorate at least some of the stressors

that are known to interfere with learning in professional school

environments. The course was designed to help students from

the health sciences manage anxiety and stress. Initially, students

were second-year medical students and graduate nursing

students. Later the course was opened to pharmacy students

and, on a space-available basis, to a few students from other

professional schools such as public health and education. The

objective of this study was to determine the extent to which

former medical, pharmacy and nursing students retrospectively

viewed the course’s MBM content and experiences as having been

valuable for their personal and professional development, and

for coping with chronic stress. It was also designed to determine

whether the former MBM students would recommend similar

instructional experiences for others within their profession. The

U_ course, Introduction to Mind Body Medicine – An Experiential

Elective, was adapted from a mind body skills program offered by

the Center for Mind-Body Medicine and was similar to a course at

Georgetown University Medical School [22]. Initially, the U_ MBM

course was offered exclusively to medical and graduate nursing

students. Later, we included pharmacy students. As a ‘conjoint’

course, the founding faculty members were from more than one

professional school. As the course evolved, volunteer faculty also

came from a variety of healthcare professional practices.

The UW mind-body medicine (MBM) course focused on

activities that included various ‘mindfulness practices (mindful

meditation, mindful eating, walking meditation), various other

meditation practices (quiet meditations, shaking meditations,

guided imagery, yoga), as well as discussions about nutrition,

mirror neurons, and spirituality. It was apparent from the

outset that certain activities ‘resonated’ with some students,

but not with others, and vice-versa. Since 2010, depending on

faculty availability, from 2 to 4 concurrent sections of the U_’s

multidisciplinary MBM course were offered during both the

autumn and winter quarters. Each small group consisted of

between 8 and 12 students. Each section of the course met for

eight weeks for 3-hour sessions, with one or two faculty ‘guides,’

most of who were volunteers. Typically, sessions opened with a

brief meditation, a ‘check-in’ and then an activity that provided an

experience aimed at exploring mind-body connections. Listening respectfully without interruptions was the rule. Students were

reminded that they were there to experiences mind-body

practices and to engage in self-exploration, not to fix others.

Modeling the confidentiality of the healer/patient relationship,

we emphasized that anything that transpired during the sessions

was to be held in complete confidence.

Each week’s session focused on students engaging in, one or

more MBM experiences. Each weekly session began with a brief

mindfulness meditation. This meditation was followed by each

participant “checking-in” with a summary of how the previous

week had gone for them. These brief check-ins provided the

group with individual student’s and guide’s overviews of

their successes or challenges during the previous week at

incorporating mindfulness and other mind-body practices,

including exercise, into their daily routines. The check-in allowed

students and the faculty guides to think about and share with

their course colleagues their experiences and related feelings in a

nonjudgmental, supportive environment. The faculty facilitator/

guides participated fully in the group process and presumably

modeled these behaviors, sharing their challenges in keeping

up with the “mindfulness” homework activities. After the checkin

period, the week’s focal point subject was briefly presented,

sometimes with a brief PowerPoint presentation followed by

group discussion and Q&A. The remainder of the sessions, usually

70 to 75% of the time, was devoted to experiential practice with

a variety of meditation techniques and guided imagery. We also

provided a closing meditation at the end of each session.

As a prelude to preparing genograms, students were

encouraged to contact significant family members (such as

parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents). The goal was to seek

information about family members’ views of family strengths,

beliefs, values, stressors, diseases and relationships about which

the students might not have been aware. A genogram is a family

tree that highlights one’s family’s strengths, beliefs, and values,

stressors, diseases, as well as the extent to which relationships

were close, distant, cut-off and/or conflicted. A review of

genograms is available online [26]. During the last three

sessions, a portion of in-class time was provided for each student

to prepare and then share his or her family’s three-generation

genogram. Over 95 percent of participants chose to present

their genogram and share any insights they might have gained

regarding the extent to which their family’s methods of coping

with and managing stress. Insights about how their experiences

in their families shaped their ability to cope with chronic stress

were shared with the group.

An earlier pre- and post-course effectiveness study

of the UW

MBM course indicated that the course was needed and effective

and that it had lasting short-term impacts. The intervention and

comparison groups, which differed significantly with respect to

anxiety levels at the beginning of the mind-body course (time 1),

were indistinguishable from each other 10 weeks later at the end

of the course (time 2). Three months after the course concluded (time

3), the observed lowered anxiety levels in the intervention

group were sustained [19].

Medical, nursing, and pharmacy students had priority for

registering for the course. Students from other professional

schools were allowed to register on a space-available basis. We

excluded students from other schools from the analyses. After

identifying the pool of health professional students who had

completed the course during the 7-year timeframe between

2010 and 2017, we embarked on the process of locating valid

emails. We finalized a list of 319 “likely valid” emails.

We designed an online follow-up survey to help ascertain

former MBM students’ insights into the effectiveness of the

course for mitigating the effects of chronic stress. The survey

assured potential respondents of confidentiality and was

approved by the U_ Human Subjects Committee. Four related

items queried about attribution of course impacts. These were

1. Would you attribute significant positive long-term

impact(s) on you personally as a result of your having elected

to take our MBM Course?

2. Would you attribute significant positive long-term

impact(s) on the way you professionally practice as a result

of your having elected to take our MBM Course?

3. Would you recommend a similar experiential course of

instruction for friends and family?

4. Would you recommend a similar experiential course

of instruction for your professional colleagues? The four

mutually exclusive, categorical response options were:

a) Absolutely yes

b) Yes, but I expected more

c) Had a slight impact

d) Absolutely not.

The survey also included eight items that asked about the

extent to which the course’s eight MBM components/concepts

helped mitigate the effects of stress.

The eight course components/concepts were: Mindfulness,

Meditation practices, Shaking meditation, Guided imagery,

Mirror neurons, Yoga, Spirituality, and Genograms. The four

mutually exclusive, categorical options were

a) Yes, very effective

b) Yes, moderately

c) Only slightly

d) No, didn’t resonate with me

For each of the eight course components/concepts, the survey

also asked about “the extent to which you have incorporated

course components/concepts into your personal practices.” The

four mutually exclusive, categorical response options were

a) Yes, very effective

b) Yes, moderately

c) Only slightly

d) No, didn’t resonate with me

Finally, we provided a response box for respondents “to offer

an entirely optional reflection about the course.

The survey was disseminated in late 2016 and early 2017

via the UW’s Online Catalyst System to 319 medical, nursing and

pharmacy students who had taken the course during the period

between 2010-2017 and for whom we were able to identify likely

still current contact information. Three automated reminders

were sent to non-responders.

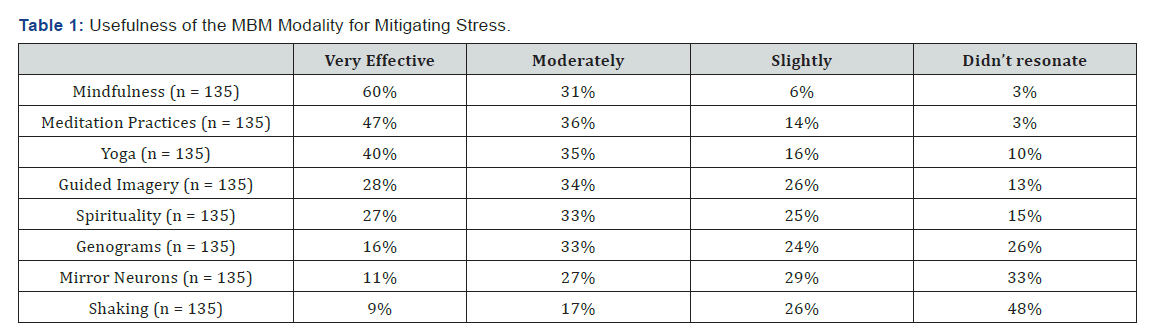

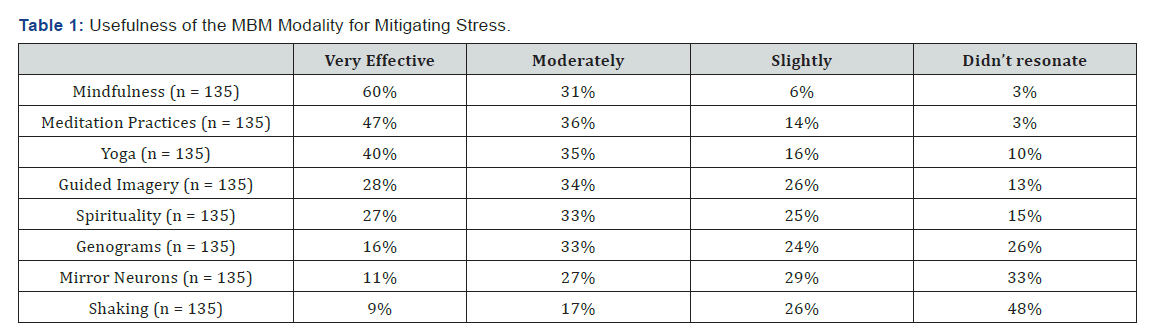

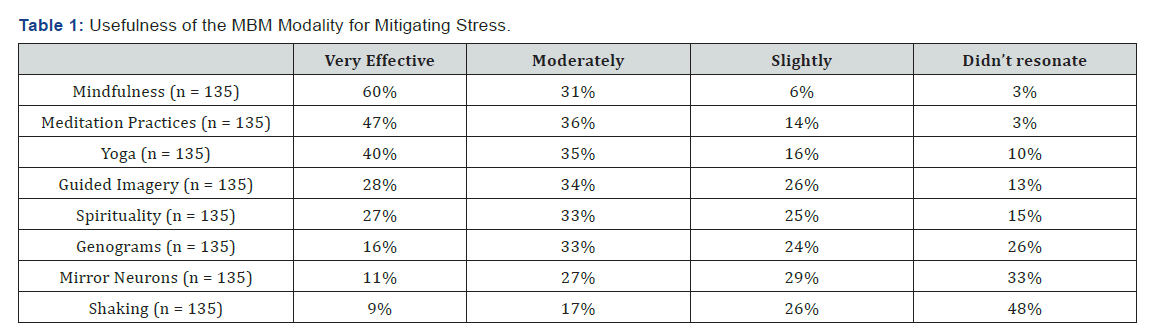

The course provided eight categories of mind/body

experiential activities. These are shown in Table 1 in decreasing

order based on the percent indicating that the category was

“very” effective for mitigating stress. Overall, the most effective

activities for mitigating stress were mindfulness, meditation

practices, and yoga. These were viewed as at least “moderately”

effective by at least 75% of respondents. Guided imagery and

spirituality were viewed as somewhat less effective but were

cited as at least “moderately” effective for mitigating stress by a

majority of respondents. Genograms, information about mirror

neurons, and shaking meditation resonated only slightly or not

at all for the majority of respondents.

As shown in Table 1, over 75% of responding medical,

nursing and pharmacy students indicated that meditation and

mindfulness practices were “very” or “moderately” effective

for mitigating stress. Yoga, guided imagery, and spirituality

for stress mitigation were viewed as “very” or “moderately”

effective by just over 60% of responding medical, nursing and

pharmacy students. Discussions of the importance of family

history, experiences and values in understanding stress origins,

as reflected in student-generated and shared genograms, was

viewed as “very” or “moderately” effective by 40% of responding

medical, nursing and pharmacy students. The role of “mirror

neurons” in listening to, for understanding the feelings of others

(empathy), and for communicating feelings was cited as “very”

or “moderately” effective by approximately 25% of responding

medical and pharmacy students but by over 60% of the nursing

students. We introduced the concept of mirror neurons by

viewing a NOVA Science Now program that originally aired on

25 Jan 2005. Discussion of mirror neuron implications to mindbody

considerations followed. The NOVA Mirror Neuron Video is

no longer available for streaming from PBS but it is available on

YouTube.

Shaking meditation, promoted by OSHO as kundalini

meditation, involves a series of body movements including

shaking, dancing, and quiet meditation guided by music. It

is a technique that may challenge the ‘comfort zone’ of many

individuals and did not resonate with half of the respondents.

The music is available on CD or online. [27] A number of websites

now promote and present discussions and video demonstrations

of shaking meditation [28,29].

Figure 1 presents the extent to which former medical,

nursing, and pharmacy students reported that the top-rated

“mindfulness” practices helped students mitigate the effects of

stress. The majority of all three types of clinicians indicated that

the course had been “very effective” in helping them mitigate the

effects of their stress (pharmacy students 74%, medical students

54%, and nursing students 53%). Ninety-eight percent (98%) of

medical and 100% of pharmacy respondents indicated that the

course was “very” or “moderately” effective for mitigating the

effects of stress. Eighty-four (84%) of nursing students indicated

that “mindfulness” practices were “very” or “moderately”

effective for mitigating the effects of stress. Two medical student

respondents (2%) indicated that mindfulness did not resonate

with them.

Very similar results were obtained for “mediation practices”.

The vast majority of former medical, nursing, and pharmacy

students reported that “meditation practices” helped them

mitigate the effects of stress. The majority of former medical,

pharmacy, and nursing students indicated that the course’s

meditation experiences were “very effective” in helping them mitigate the effects of their stress. All former pharmacy students

indicated that the course’s meditation experiences had been

either “very” or “moderately” effective at helping mitigate the

effects of stress. Similar percentages for medical and nursing

students were 91% and 84%, respectively. Four percent of former

medical students (4%) indicated that the course’s meditation

practices did not resonate with them.

Figures 2 presents the extent to which former medical,

pharmacy and nursing students attributed long-term course

impacts on their professional practice. When asked whether

as a result of having elected to take this course they would

attribute significant positive long-term impacts on the way

they professionally practice, all former medical, pharmacy

and nursing students responded that the course had at least a

“slight impact” on their professional practice. The percentages

of former medical, pharmacy and nursing students indicating

“Absolutely yes” that they would attribute significant positive

long-term impacts on their professional practice, were 46, 59,

and 32%, respectively.

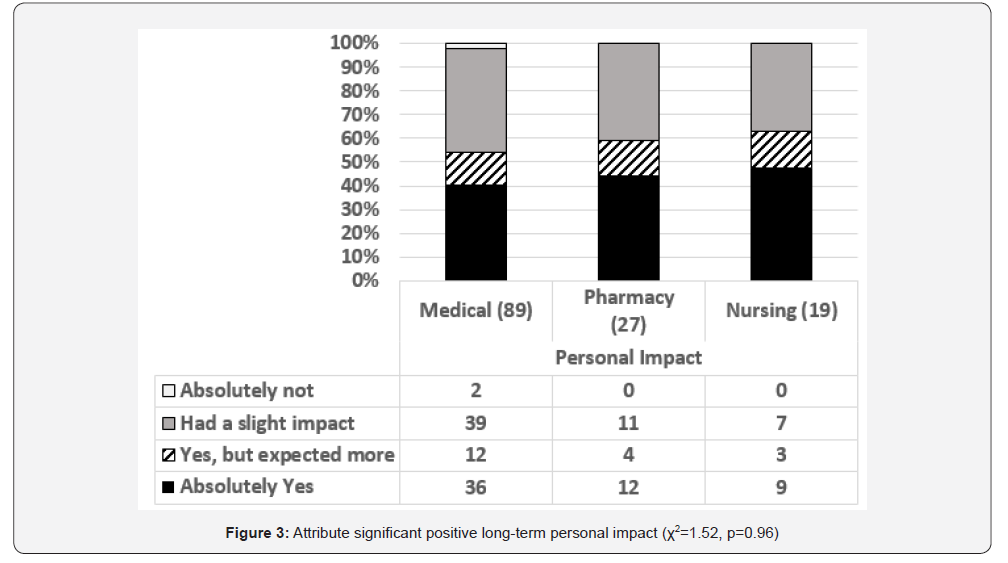

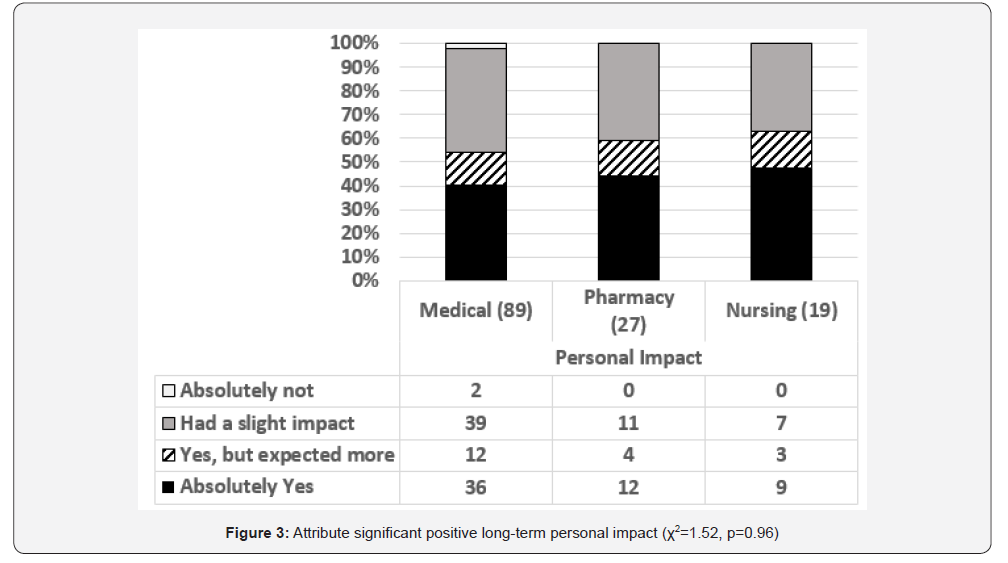

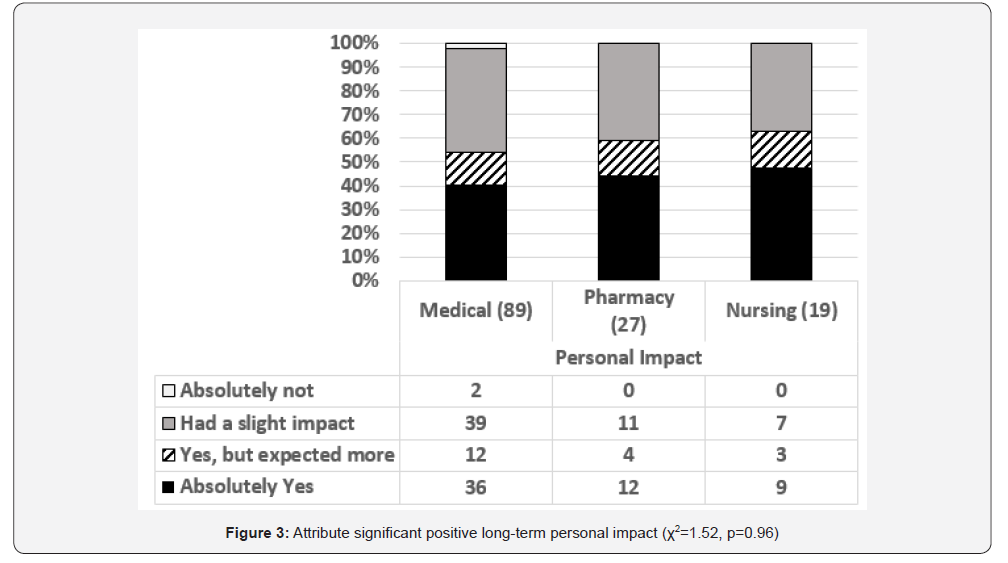

Figure 3 presents the extent to which former medical,

pharmacy and nursing students attributed long-term course

impacts on them. Two medical students (2%) indicated that the

course’s meditation practices did not resonate with them. The

percentages of former medical, pharmacy and nursing students

that indicated “Absolutely yes” that they would attribute

significant positive long-term impacts to the course’s meditation

practices were 40, 44%, and 47%, respectively. The percentages

of former medical, pharmacy and nursing students that indicated

“Absolutely yes” that they would attribute significant positive

long-term impacts or “Yes, but I expected more” were 54, 59,

and 63%, respectively. Respondents from medicine, nursing and

pharmacy highly recommended a similar experiential course

of instruction for their professional colleagues. Over 70% of

the former medical, pharmacy and nursing students responded

“Absolutely Yes” they would recommend a similar experiential course to their colleagues for professional colleagues (medical

72%, pharmacy 85%, and nursing 86%).

Overall, the majority of former health profession students who

participated in the course reported positive long-term impacts.

The most effective of the MBM activities for mitigating stress

were mindfulness, meditation practices, and yoga. Mindfulness

was also the approach that was most commonly incorporated into

personal practices. The majority of respondents also reported

that guided imagery and spirituality were viewed as helpful and

at least “moderately” effective for mitigating stress. Genograms

and information about mirror neurons resonated with less than

half of respondents. By sharp contrast, the shaking meditation

was the least likely to be incorporated into personal practices;

it and was viewed as being “very” or “moderately” effective by

fewer than 30% of respondents. Shaking may have been outside

the comfort zone of some students.

For the majority of former UW medical, nursing, and

pharmacy students, experiences related to the top-rated practice

category of mindfulness indicated that the course had been “very

effective” in helping them mitigate the effects of stress. The vast

majority of respondents viewed mindfulness practices as “very”

or “moderately” effective for mitigating the effects of stress. That

said, two medical students (2%) indicated that the course did not

resonate with them at all concerning the mitigating the effects

of mindfulness. All pharmacy or nursing students indicated

that mindfulness practices were at least “slightly” effective for

mitigating the effects of stress. The overwhelmingly positive

perceptions of the effectiveness of mindfulness practices provide

strong support for offering mindfulness experiences to students

in these health professions, at least as a part of elective offerings.

It should be said that in this study we examined perceptions

of effectiveness, not objective measures of the effectiveness

of mindfulness. A cautionary note; some psychologists,

neuroscientists and meditation experts contend that hype about

mindfulness may be outpacing science [30].

All former pharmacy students and over three-quarters of

former medical and nursing students reported that the course’s

meditation experiences were at least “very” or “moderately”

helpful for reducing the effects of stress. Again, former medical

students were slightly less enthusiastic but still overwhelmingly

positive about the utility of meditation experiences for helping

them mitigate the effects of stress. All respondents attributed

some long-term course impacts on their professional practices.

Likewise, the vast majority of respondents attributed long-term

personal impacts to the course, although 2% of medical students

indicated that they did not attribute any significant personal

impacts to the course. Most importantly, the vast majority of

these former MBM students from the three health professions

indicated “absolutely yes” they would recommend such a course

for their colleagues.

This study provides evidence that mind-body techniques,

particularly mindfulness, when offered in an elective, interprofessional,

small group setting, are viewed positively over time

and may help reduce the high levels of stress encountered within

the healthcare professions. These results suggest that skillsbased

mindfulness courses for health professions students may

serve to reduce burnout in future clinicians. At the University of

Washington we are fortunate to have several health professional schools on the same campus. Some of our nursing students

had many years of clinical experience whereas most medical

and pharmacy students were relatively early in their training.

The result was inter-professional and inter-generational

communication between diverse students from different schools.

From the authors’ point of view, this was an important part of the

small group experience. Insights into the personal viewpoints of

students of other professions, as gained in small group settings,

may help lay the foundation for more mutually empathic ‘team’

approaches to healthcare in the future, but that remains to be

seen. There have been efforts in various institutions to train

students together for technical details of clinical practice, but

evidence-based results regarding health care processes and

patient outcomes have not been definitive [31].

The majority of our former UW students absolutely

recommend that such experiential MBM courses be offered to

help students cope with chronic stress. We hypothesize that

our findings should generalize to other health professions such

as physician’s assistant, dental, physical therapy, rehabilitation

education and the like. Our results support the contention

that experiential mind-body, stress management courses

would contribute to the development of more resilient health

professionals as they enter and pursue their professional

practice years.

Respondents had completed the course anywhere from 7

years ago to 6 months prior. Thus, it is possible that with the

passage of time some of the reported longer-term impacts might

have been slightly lower had all students taken the course 7

years prior to the study. There is likely some attrition bias given

the number of students who were found to have non-working

emails. This may have resulted in an over-representation of

students who took the course more recently.

Health professional education and practice is well known

to be challenging and highly stressful. This study suggests that

providing mind-body medicine experiences during the formative

educational years of health professionals is likely to enhance

their ability to cope with personal and professional stress.

Therefore, we recommend that health professional schools offer

elective, experiential MBM courses. We also recommend formal

training of faculty members to be “champions” of such courses

and provision of dedicated quiet space, stationery supplies,

music, multiple yoga mats, etc.

Multi-institutional follow-up studies that compare and

contrast results from similar courses at different locales, and

perhaps at different points in time, would certainly expand

upon our findings. It would be beneficial to follow-up students

who have completed similar experiential MBM courses over

longer periods of time. These would more precisely quantify how the impressions and effects are impacted by passage of

time and years of clinical practice. Future study designs should

consider incorporating validated burnout, stress, and anxiety

assessments to quantitatively measure the effects of such

courses over longer periods of time and inclusion within the

study designs of comparison/control groups [23]. It would be

useful as well to evaluate with mixed method assessments the

subjective preferences of the students for the different mindbody

practices taught. This would help clarify those practices

from which students would be most likely to benefit. Finally, it

could be useful to know the extent to which those who take such

experiential courses share learned skills with their colleagues,

staff, and/or patients.

The modest resources that elective MBM courses require

to enhance clinician resilience would likely be worth the

investment, at least for those students who feel they are being

overwhelmed by the inevitable challenges and stresses they are

only beginning to encounter; stressors that will persist as they

engage in their chosen professions.

Comments

Post a Comment