A Mixed-Method Analysis of an Equine Complementary Therapy Program to Heal Combat Veterans- Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers- Journal of complementary medicine

Abstract

This study presents a mixed-methods analysis to

understand the healing experiences of veterans diagnosed with

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a heart-centered complementary

therapy horsemanship program. This therapy was designed to address PTSD

symptoms and involved weekly activities involving small group and

one-on-one interactions with a horse and riding instructors. Previous

work by our group found that this program provided significant

improvement in the psychophysiological health of the participants. In

this stage, the following research question was addressed: How did the

veterans describe their healing experiences with horses in the program? A

cohort of 9 combat veteran participants were first analyzed using the

positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) before and after each

weekly session of the 8-week program. The PANAS results revealed a

significant change in positive affect starting in week 2 (paired t test,

t = -2.76, P = 0.025). Weekly writings from participant’s journals were

analyzed qualitatively using a phenomenological method of inquiry. This

analysis resulted in a narrative integration of the significant

statements, formulated meanings, and a cluster of themes. The themes

centered around positive impact, connection with a horse, being present,

horse mirroring, translating, trauma, and power dynamics. These themes

described positive behaviors that resulted in reduced PTSD symptomology

and promoted the healing phenomenon.

Keywords: PTSD symptoms; Veterans; Horsemanship; PANAS; complementary treatment; Mix-methods research; Equine assisted therapy

Abbrevations:

PANAS: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PTSD: Post Traumatic

Stress Disorder; EPE: Equine Partnered Experiences; TBI: Traumatic Brain

Injury; HRV: Heart Rate Variability; HOH: Heart of Horsemanship

program; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

Fifth Ed.; PCL-5: PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; SSNI:

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors; EMDR: Eye Movement

Desensitization Reprocessing

Introduction

PTSD

There are more than 500,000 veterans who

participated in various US military wars over the past 60 years who

suffer from symptoms diagnosed as PTSD and traumatic brain injury (TBI).

It is becoming clear that military personnel exposed to combat

operations are at an increased risk for PTSD [1]. According to Makinson

& Young [2], “PTSD is a mental disorder characterized by a sudden

onset of symptoms due to environmental exposure to a psychologically

stressful event such as war, natural disaster, or sexual victimization”.

The DSM-5 handbook describes intrusion symptoms, avoidance, negative

alterations in cognition and mood, and alteration in alertness and

negativity [3]. Intrusion symptoms include the reoccurrence of the event

in thoughts, dreams, illusions, or flashbacks. Those suffering from

PTSD will also avoid thoughts and feelings connected to the event/people

or places that trigger recollections of the trauma and possess

negative alterations to include negative beliefs about oneself,

diminished interest in social activities, or detachment from others.

Veterans will express alteration in alertness and activity and exhibit

irritable behavior, insomnia, and hypervigilance. Most importantly is

that veterans who suffer from the impacts of PTSD experience an overall

impairment in their day-to-day living.

Treatment options

In 2010, the Department of Veterans Affairs and

Department of Defense released their recommended guidelines for

treatment of PTSD. Of many modalities for treatment, exposure therapy,

specifically prolonged exposure therapy, was recommended as an

evidence-based treatment option. Other modalities included: cognitive

processing therapy, stress inoculation training, treatment with

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI), and eye movement

desensitization reprocessing (EMDR) treatment [4]. Until recently,

equine therapy has not been the center stage of treatment options

available for veterans.

Previous research

The authors have been conducting research with

military veterans since 2015 using equine therapy as a nonpharmacological

complementary approach to healing. The first

research stage employed a quantitative assessment measuring

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) to determine the physiological

changes occurring during a heart-based equine therapy program.

Veterans were also given a psychological self-assessment to

determine a positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) of their

equine experience. Results were significant from the quantitative

perspective demonstrating a positive wellbeing outcome for

the participants [5]. To endeavor in further inquiry, the authors

shifted their emphasis to a mixed-method analysis based on the

data from weekly journaling and recorded observations.

History of healing veterans with horses

Since the fifth century B.C. horseback riding was used for

rehabilitating wounded soldiers [6]. For many years, animals have

been used for the therapeutic benefit of humans in a variety of

settings. For example, domestic animals are used to help medically

ill children in hospitals and the elderly in nursing homes, but it was

not until the 1960s that horses were used in the United States for

therapeutic purposes [7]. Horses have proven effective in working

in partnership with humans to aid the process of healing from

trauma, grief, depression, and other emotional challenges. Unlike

humans, they are not capable of hiding their emotions. In fact,

they are primarily emotional beings and respond to the stimuli

produced by emotional energy which begins from the heart [8].

Horses have abilities to interact with and heal humans. Like

humans, horses live in social herds. Horses are prey animals

making them hypervigilant to the intentions of those in the

environment for their survival. Horses are quick and instinctual

in sensing the emotional field around them. This helps encourage

veterans to develop trust, to operate with integrity and fairness

and to be clear in communication and intention. Horses enable

veterans to accept criticism and self-judgment. This had led to

veterans experiencing less anxiety, stress, emotional upheavals

and feeling more confident in the decisions they make [5].

Experiences with horses provides a safe place for addressing and

shifting the pain and suffering associated with PTSD.

Materials and Methods

findings were significant and a paper was published in the

Military, Veterans and Family Health Journal [5] regarding the

quantitative results. This paper provides an emphasis on the

qualitative analysis relating to the deeper human aspect of what

the experience meant to the veterans as they developed strong

bonds and partnerships with the horses and as a group.

Participant selection

The participants were recruited from a Southern California

Veterans center. The director of the Veterans Center was

instrumental in identifying candidates who were working with

traditional counseling therapy either in group or individually and

referred them to the horsemanship program. Space was limited to

nine in the cohort and the study team did not discriminate based

on gender, age, or which war situation contributed to their PTSD.

The ages ranged from 22 to 68 years and from Iraq to Vietnam

deployments. We purposely did not request their PCL-5 [10]

checklist scores or have them take any of the VA assessments

regarding their level of PTSD.

All participants signed liability releases, consent forms, and

photo release forms. They were informed regarding the research

protocol and had the option to not participate. However, all were

eager to participate and agreed to the weekly data collection

that included taking a positive and negative affect instrument

known as the PANAS (a validated instrument) [10] to determine

if they would self-report improvements in symptoms associated

with PTSD because of participating in the heart of horsemanship

partnership program.

Study design

The study was conducted over eight weeks with one half day

session each week. Participants arrived at the ranch in a van from

the Vet Center or separately in their own vehicle. Upon arrival

they would complete the 20 question PANAS questionnaire. The

wranglers/instructors, veterans and two researchers would

meet for about half hour in a circle to brief the group for the

day’s suggested activities. Each week included an opening circle

and meditation where participants checked in. Participation

was voluntary but most offered reflections of their current

psychological state. The meditation focused on attentiveness of

the heart and their body. A crystal bowl tuned to the heart was

played to conclude the opening circle and then the veterans left

the circle to go bond with and halter their horse. The sessions

ran from 9 am to 12 noon, with two hours of horse engagement

activities. We concluded with a closing circle at the end of each

3-hour session to allow for debrief and participant insight sharing.

The crystal heart bowl was played as a final note and the veterans

departed- often exchanging hugs and words with each other and

the wrangler/instructors.

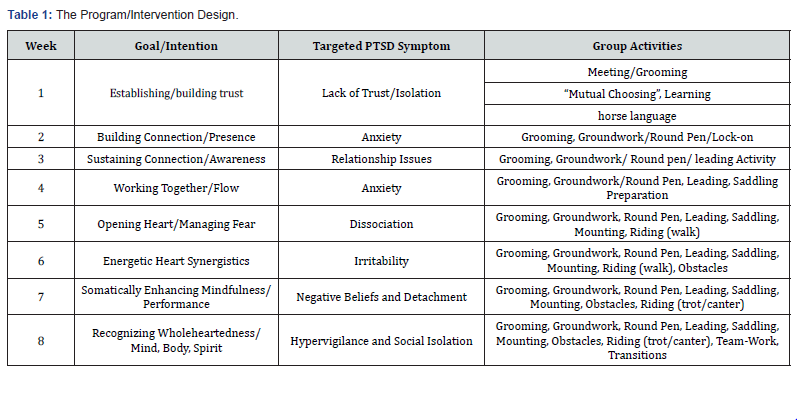

Specific symptoms associated with PTSD guided the

curriculum design for each session and is outlined in Table 1. Each

veteran initially selected their own horse based on a perceived

felt energetic connection. They continued working with their

selected horse on a continuous weekly basis. Participants also

had an experienced individual wrangler/instructor who helped

guide them in getting acquainted with their horse and to ensure

their learning and safety. Sometimes veterans would join in all group activities such as obstacle training, and other times they

would work privately with their wrangler/instructor. The goals/

intentions of the weekly sessions were known and how each

veteran addressed them varied from individual to individual.

The purpose of this phenomenological study is to understand

how the interaction with equine partnered experiences (EPE)

helped veterans with PTSD heal. We addressed the following

qualitative question: How did veterans with PTSD describe

their healing experiences in a group structured heart-centered

horsemanship program?

Data analysis

Analysis was guided by the research question, the structured

weekly journal prompts, and Colaizzi’s [11] phenomenological

method of inquiry. There are seven procedural steps to Colaizzi’s

[11] method of data analysis which include

a) reading all the participant’s weekly journal entries to

acquire a feeling for them

b) extract significant statements from the transcriptions

that are related to the veteran’s self-reported healing process

c) formulate meanings or codes from the significant

statements.

d) repeat step 3 for each participant’s journals, and then

place the codes into clusters of themes based on frequency.

e) integrate all the results into an exhaustive description of

the healing process and program.

f) Attempt to reduce exhaustive description into the

unequivocal statement that is an identification of the

fundamental structure of the phenomenon.

g) Return the findings to one participant in the study for

interrater checking or informant feedback.

Results

PANAS

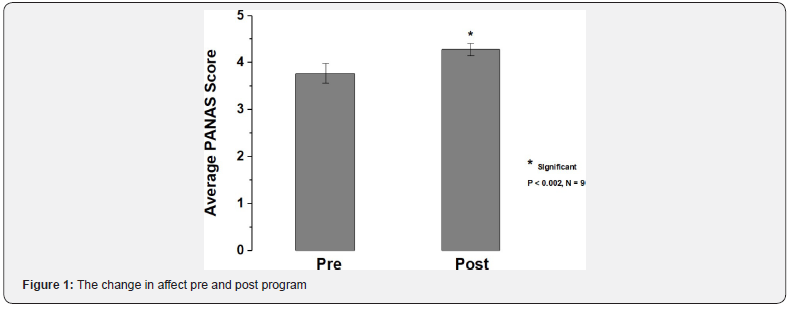

For the PANAS results, the affect scores (negative affect

converted to corresponding positive score) were averaged for the

before (pre) and after (post) weekly sessions and are displayed as

a bar graph in Figure 1. The subjects positive outlook improved

over the course of the program. A significant change in affect

occurred at week 2 using a paired t test (t = -2.76, P = 0.025) and

stayed significantly different for the rest of the program (t = -4.37,

P = 0.002). Week 1 showed improvement, but was not significantly

different (t = -2.00, P = 0.085, data not shown).

Qualitative coding meaning

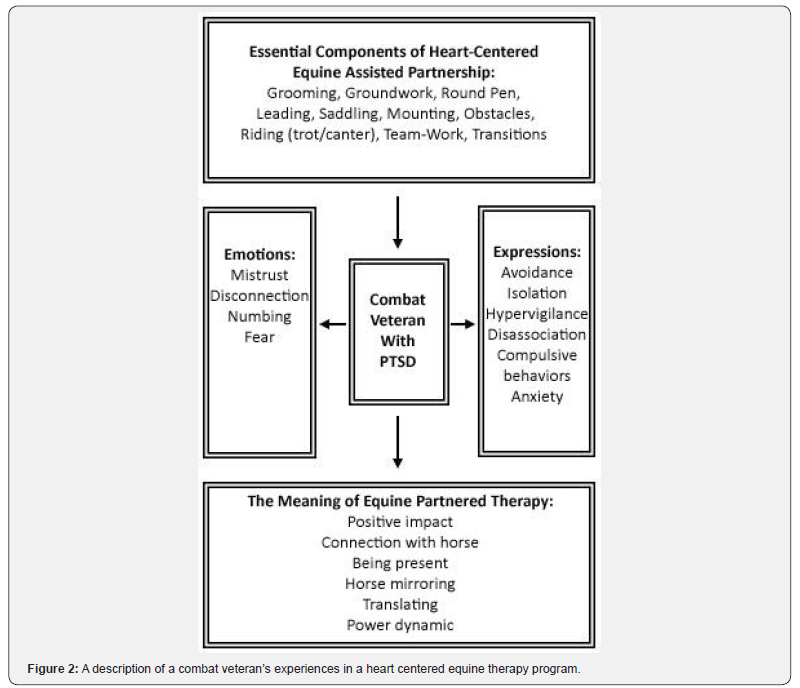

Based on a related study description of hospital-related fears

for small children [12], the experience of a combat veteran with

PTSD in a heart-centered equine partnered therapy program

was outlined in Figure 2. These experiences in an equine therapy

program consisted of essential curriculum components, the

emotions and expressions elicited from the veterans, and the

meaning associated with the experience.

Essential components of heart-centered equine-assisted partnership

This study intentionally designed heart-centered curriculum

components to a heart-centered equine partnership around

the symptomology of PTSD. These included activities such as

grooming, groundwork, round-pen interactions, leading, saddling,

mounting, managing obstacles, riding (trot/canter), teamwork

exercises, and making riding transitions. These program

components are described by week in Table 1.

The ways in which combat veterans expressed themselves during the equine interaction

When each veteran interacted with their individual horse he

or she described emotions of mistrust and feeling disconnected

from the world. The veterans also described a feeling of emotional

numbing, unable to express his or her feelings in their daily

functioning.

Participants expressed themselves in behaviors

related to

avoidance and isolation, choosing to be alone with their horse versus

with the group. They explain feeling outside of their bodies

in a dissociative state disconnected from the present moment.

Compulsive behaviors and being hypervigilant to those around

them and his or her surroundings were shared consistent with

typical behaviors for the diagnosis of PTSD.

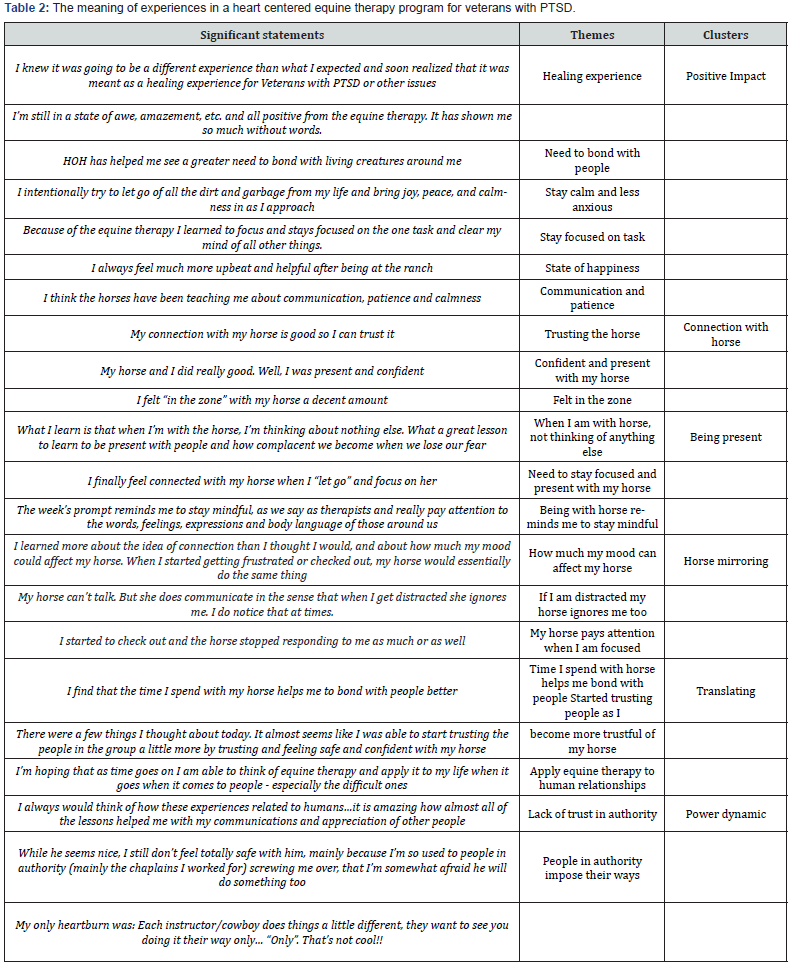

The meaning of a heart-centered equine partnered experience to combat veterans with PTSD

The meaning of an equine-partnered experience for combat

veterans with PTSD are defined by several significant statements

that consisted of six main clusters that came out of the qualitative

analysis: positive impact, connection with horse, being present,

horse mirroring, translating, and power dynamics (Table 2).

Positive impact

The cluster of positive impact consisted of six themes

describing an overall positive impact of participation. The theme

of healing experience describes how many of the veterans found

interaction with his or her horse to be a healing process. The

program also reaffirmed veterans need to bond with people. and

find connection. Staying calm and less anxious were intentionally

challenged to help the veteran find more peace, joy and calmness

to the experience, but also to their lives. Intention to focus on task

helped clear the veterans mind from other distractions in his or

her life. Finally, themes of communication and patience and overall

state of happiness were evident as the horse interaction allowed

the veteran to better communicate and provide an overall sense of

peace and happiness.

Connection with horse

The feeling of connection is one that many of us strive for.

Both horses and humans are social species, seeking connection

to others is an important part of our emotional and physical

well-being. Connection is a feeling, and so it can be described in

different ways. Veterans describe this connection as an awareness

of a presence with a sentient being. They describe that having a

connection allows them to trust his or her horse. And participants

feel accomplished when they are present and confident in their

ability with the horse. Over the course of the program, veterans

explain feeling in the “zone” in which they felt a oneness oftentimes

without thinking or trying too hard to do so.

Being present/mindfulness

The cluster being present/mindfulness explains how the

veteran felt grounded, in the moment and totally focused on the

present moment. For example, when committed to the entire

presence and behavior of the horse, the veteran forgets about

other stressors or anxieties in his or her life. They recognize that

intentional focus on the horse, allows a “letting go” to be present

around the horse. Reciprocally, being totally with the horse also

seems to reinforce personal mindfulness of those others around

him or her

Horse mirroring

Horse mirroring is the reflection of self in the horse’s emotions

and behavior. In other words, if the veteran noticed his or her

mood was poor the horse would respond accordingly poor. Also,

if the veteran bought daily living distractions such as family or

personal life into the interaction, the horse ignored the veteran.

Soon the veteran realized that the horse pays attention when the

combat veteran “shows up” to lead and is focused on the horse.

Translating

Applying program lessons to one’s personal life was described

in the cluster of themes as translating. In short, the veteran begins

to translate little lessons learned in interacting together with the

rest of his or her social world. Learning how to bond with the horse

seemed to reinforce a positive bonding with people. Similarly,

learning to overcome trust issues from his or her trauma, became

evident when the participant wholeheartedly trusted their horse.

Quite powerfully, the veteran changed psychosocially applying his

or her thoughts and behaviors to their interaction with human

relationships.

Power dynamics

Finally, for some veterans a cluster of themes around power

dynamics existed, expressing relational distrust of authority

figures such as the therapist, facilitators or wranglers. The veteran

expressed their lack of trust in authority, and that people in

authority impose their ways on them. The veteran had to change

their rigid ideas of how to do things as directed by an authority

figure, in this case the horse wranglers.

Discussion

The results offer a view of the experience and phenomena

of a heart-centered, equine-assisted partnership for veterans

diagnosed with PTSD. The PANAS results demonstrated a

significant improvement in affect. In our last study [5], it took 4

weeks to see a significant change in affect. Here we have more

evidence that it takes time (2-4 weeks) for the affect score to catch

up to the immediate change in HRV. While veterans expressed

behaviors and emotions consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD in the

qualitative observations and journaling (isolation, hypervigilance,

distrust, etc.) most participants shared positive outcomes of

participation, explained in the cluster of themes. For example,

the theme of positive impact defined by the ways in which the

participants experienced a favorable, helpful, beneficial outcome

of the program was consistent with Earles, Vernon, and Yetz’ study

[13] that showed Equine Partnering Naturally © programming

may be an effective treatment for anxiety and posttraumatic stress

syndrome for veterans with PTSD.

Similarly, participants defined and expressed their connection

with their horse. Some felt most connected when just standing or

walking with the horse while some connected while grooming. The

most common description of connection were moments of moving

in unity, a feeling of oneness and togetherness. Horse to veteran

connection has previously been documented in the Saratoga

War Horse Project [14] in which the Connection methodology:

nonverbal language of the horse in a predictable, sequential, and

repeatable method was used with a combat veteran to build a

horse-human connection with positive psychological functioning

outcomes and reduced PTSD symptomology.

Horses, are highly social, nomadic prey animals. They embody

many of the attitudes and skills that some humans spend their

lives searching for. One of the pluses of being “in the moment” is

the ability to act quickly in the face of danger, and sometimes more

importantly, to be able to let it go and go back to grazing.

Participants spoke of “being an outsider looking in”

and “losing

touch with reality”. This form of avoidance which presents itself as

dissociation or emotional numbing is common for survivors of

trauma [15].

Participants describe a realization in working with horses

that to form connection, stay present, and manage dissociation

they need to focus and concentrate on one thing at time. Zerubavel

and Messman-Moore [16] summarized well these phenomena.

Mindfulness is a strong treatment for dissociative behavior as

it removes one from the present moment, while mindfulness

cultivates the ability to stay in the moment.

Another cluster reported was horse mirroring. Zugich, Klontz,

and Leinart [17] describe the horse as mirrors in which they can

“provide accurate and unbiased feedback, mirroring physical

and emotional states of the veteran, providing clients with the

opportunity to raise their awareness and to practice congruence

between their feelings and behaviors”. Veterans describe a lack of

presence impacted his or her horse’s behavior, providing real time

feedback helping the veteran autocorrect and stay present with

both his or her feelings and behaviors.

One of the most salient findings of the study was the way in

which participants transferred their learning from the program

and his or her horse and hoped to use the new awareness in their

lives. A parallel study

[18] using outdoor based adventure experiences to treat

veterans with PTSD found similar findings regarding veterans’

renewed ways of translating the experience to their relationships.

This is similar to a recent equine related study [19] for student

veteran nursing students who translated interactions with horses

to their personal and academic lives.

Finally, an unexpected finding was concern around power

and authority as veterans described a lack of trust and frustration

at times with the supervising clinical therapist and wranglers

involved in the group facilitation. Johnson and Lubin [20] argue

that this type of transference reaction to clinical leadership will

also reflect past experience with authority especially relative to

the trauma. And this lack of trust in authority and intolerance

of imperfection is documented in Alford, Mahone & Fielstein’s

[21] work with Vietnam veterans with PTSD. Alternatively, some

participants respected and trusted authority, consistent with

Turchik and Wilson’s [22] research on military obedience to

authority.

Special considerations

Moving forward it’s crucial that health care practitioners and

educational institutions be trained in cultural competency to

understand veteran populations. What may seem like a defiance

of instruction might be a

lifesaving way of “being” to a veteran. One veteran described

his frustration in being asked to look forward in working with

his horse instead of at his feet. Researchers learned later he

had worked in explosives detection and his squad’s lives were

dependent on his looking down. He had carried this attitude with

him into his civilian way of being. Atuel and Castro [23] provide

a strong overview of military cultural competency to include

military culture as it applies to therapeutic work for veterans.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the goal of this study was to explore the

qualitative aspects of a heart-centered equine therapy program.

Previous work by the authors showed psychophysiological

improvement in veterans participating in the 8- week program [5].

The PANAS results showed a significant improvement in affect in

the participants by the second week of the program. A qualitative

evaluation of the participants journal entries and research

observations revealed six clusters associated with the meaning

of a heart centered equine assisted partnership. The combat

veteran with PTSD may experience differing levels of interaction

and change in working with an equine partner. His or her positive

impact may be leveraged by the ability to connect with the horse,

staying present, and translating the learnings to interactions with

people. More negative expressions and behaviors due to PTSD

may be observed regarding questioning authority figures and the

symptomology related to trauma such as distrust, social anxiety,

isolation and hypervigilance.

The veteran came to recognize that his or her affect and

behavior is directly reflected or mirrored in the

horse’s behavior, such that the combat veteran became selfaware

of his or her attitudes and behaviors and self-corrected to

create a stronger bond with their horse. Thus, the phenomenon of

equine partnership creates psychosocial, physical, and emotional

changes that may serve as a non-pharmacological approach to

treatment for PTSD.

For more

articles please click on Journal of Complementary Medicine &

Alternative Healthcare

Comments

Post a Comment